| 1. ASCENT DOCUMENT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Region | Kongur Muztagh Range | |

| 2 | Valley | Chimgan | |

| 3 | Section number according to the classification table of 1999 | 11.3 | |

| 4 | Name of the summit | Peak Nikolaeva | |

| 5 | Route name | Along the southern edge to peak 5435 and along the eastern ridge | |

| 6 | Route difficulty assessment | 5B | |

| 7 | Route character | Combined | |

| 8 | Height difference along the route | 1395 m | By altimeter |

| 9 | Route length | 3850 m | |

| 10 | Length of sections | Cat. 5 diff. | 35 m |

| Cat. 6 diff. | 0 | ||

| 11 | Average steepness | Main part of the route | 38° |

| Entire route | 22° | ||

| 12 | Number of pitons left behind | Total | 0 |

| Pitons for piton hammers | 0 | ||

| 13 | Pitons used on the route | Ice screws | 74 |

| Rock pitons | 0 | ||

| 14 | Total number of artificial anchors | 0 | |

| 15 | Route duration | In walking hours | 29 h |

| In days | 4 days | ||

| 16 | Team leader | Lebedev Andrey Aleksandrovich, MSМК in tourism, Moscow | |

| 17 | Team members | Babich Mikhail Vasilievich | Saint Petersburg |

| :-- | :--: | :--: | :--: |

| Belyaeva Tatyana Andreyevna | Saint Petersburg | ||

| Maksimovich Yury Aleksandrovich | Moscow | ||

| Chkhetiani Otto Guramovich | MS in tourism, Moscow | ||

| Yanchevsky Oleg Zigmontovich | Kiev | ||

| 18 | Coach | Chkhetiani Otto Guramovich | |

| 19 | Departure to the route (from ABC) | August 16, 2003 | 8:40 |

| 20 | Arrival to the summit | August 19, 2003 | 11:30 |

| 21 | Descent to the glacier after traversing the summit | August 21, 2003 | 5:30 |

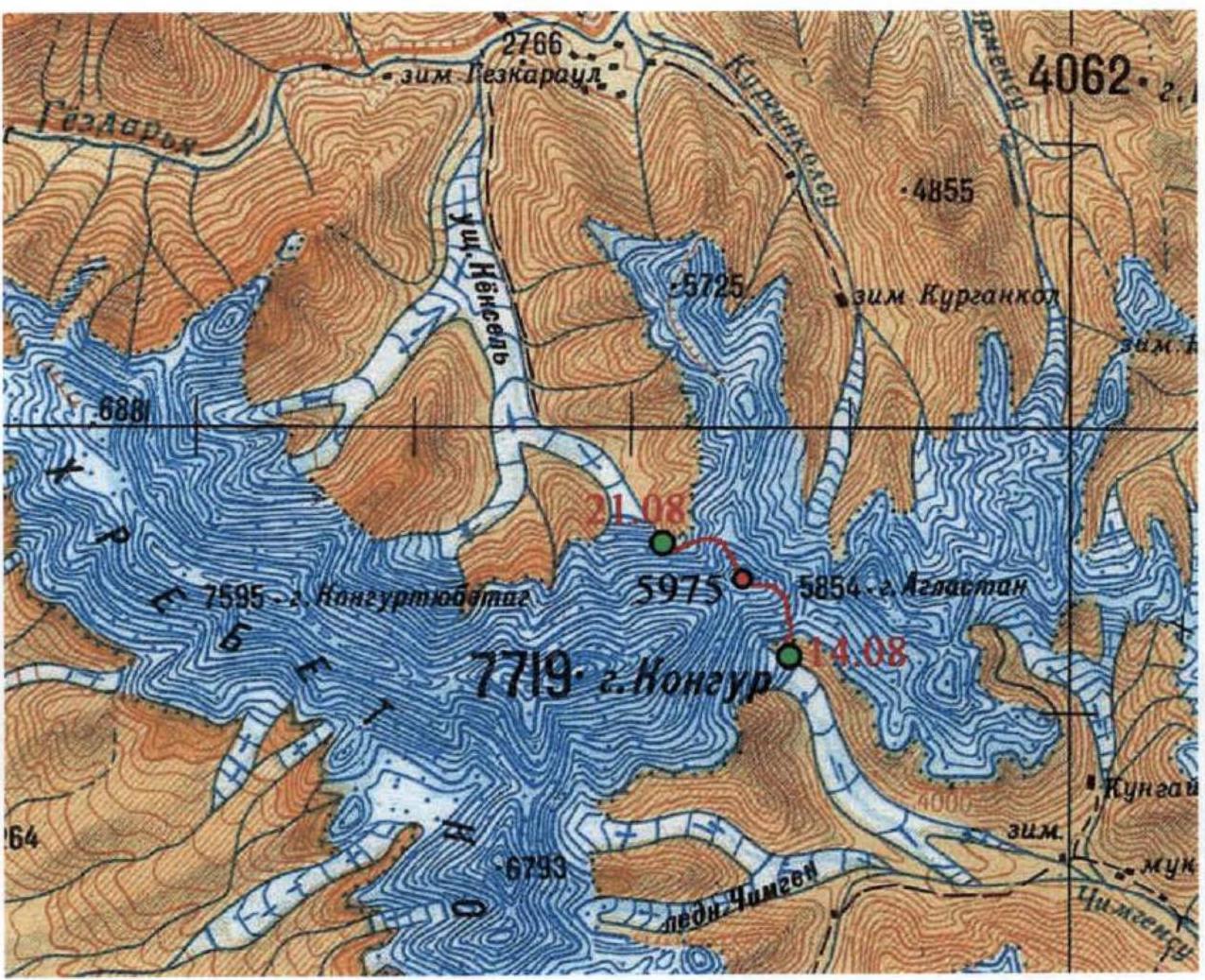

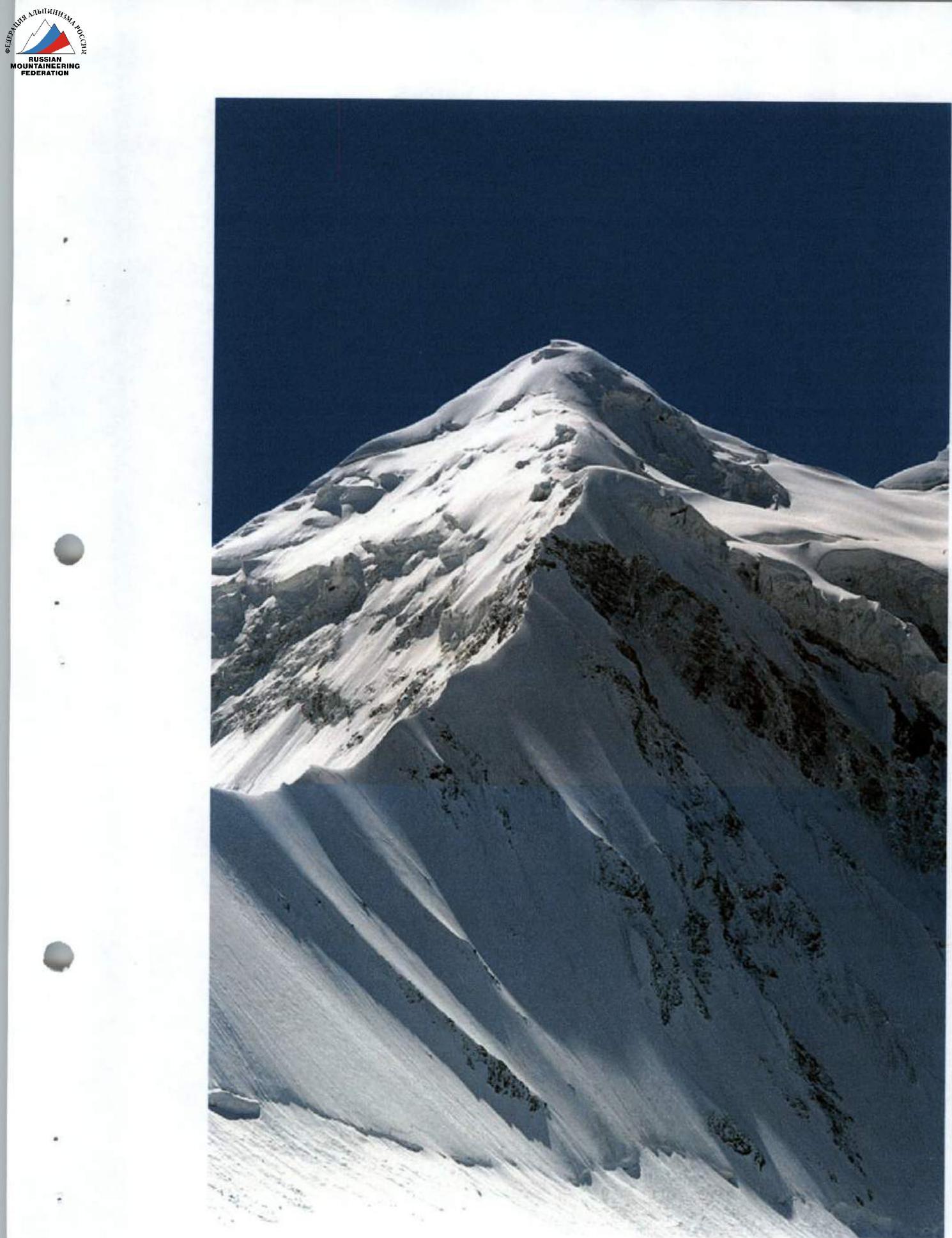

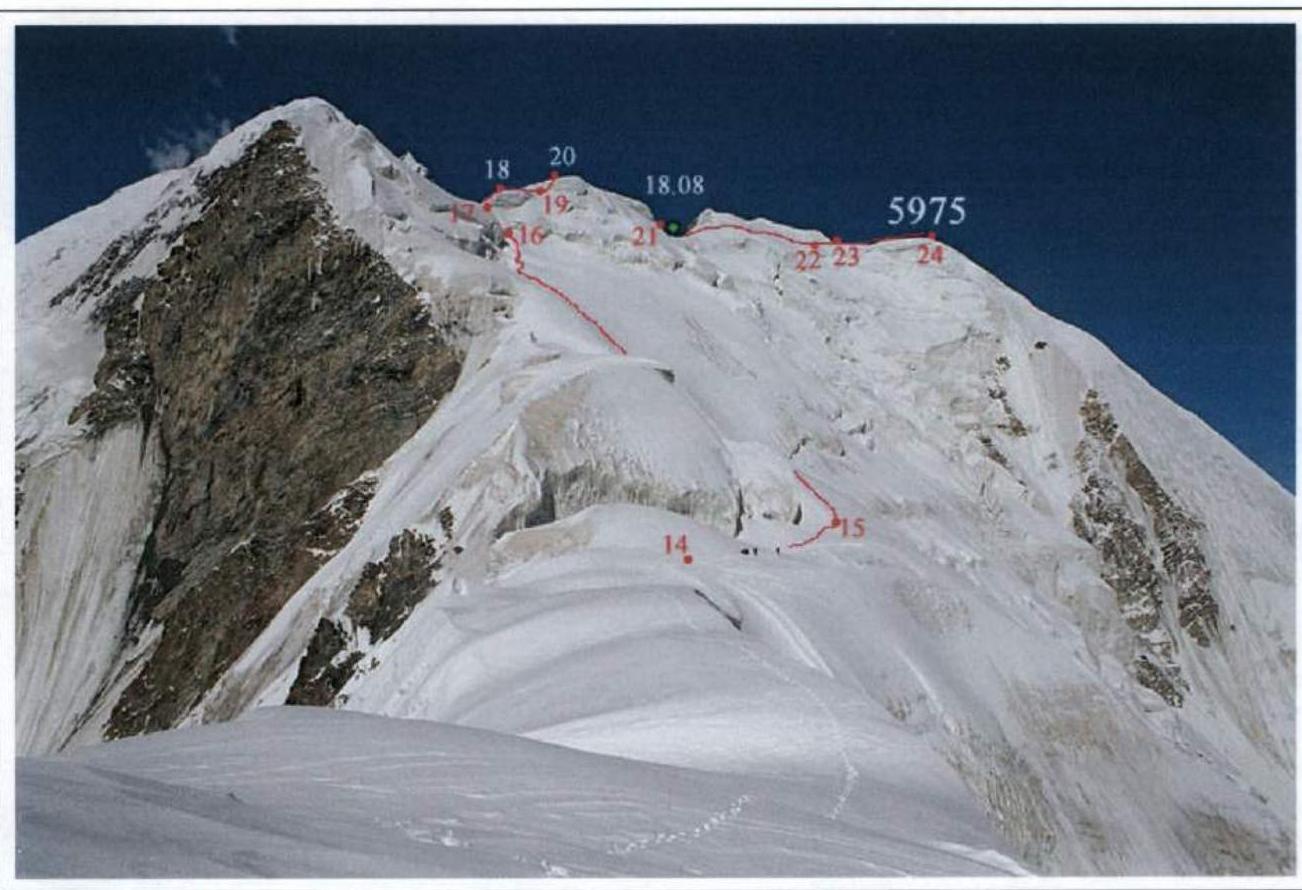

2. General photo of peak 5975

Fig. 1. View from the south (from the ascent side). The unnamed nodal peak 5975 is located east of Kongur in the Agalistan Range and is separated from the northeast ridge of Kongur by a saddle, which we conditionally call the East Kongur Pass (about 5770 m). To the north of peak 5975, a powerful spur extends, dividing the basins of the Karayalak Glacier (to the west) and the Korgan-Kul River (to the east). The spur culminates in a beautiful pointed peak Gez (5696 m), looming over the eponymous village in the Gezdarya Valley. To the west of peak 5975, beyond a deep saddle (about 5350 m), rises the rocky tower of the Agalistan peak 5630. Peak 5975 is the second highest peak in Agalistan, уступая only the unclimbed Shivakhty-III (5981 m). On the northern slope, between peak 5975 and Kongur, and to the north of the East Kongur Pass, at an altitude of 5500 to 5700 m, stretches an inclined plateau, dropping to the north with giant ice falls. The path of the failed Japanese expedition to Kongur (northeast ridge, 1981) passed along the northern edge of peak 5975 through this plateau.

Fig. 1. View from the south (from the ascent side). The unnamed nodal peak 5975 is located east of Kongur in the Agalistan Range and is separated from the northeast ridge of Kongur by a saddle, which we conditionally call the East Kongur Pass (about 5770 m). To the north of peak 5975, a powerful spur extends, dividing the basins of the Karayalak Glacier (to the west) and the Korgan-Kul River (to the east). The spur culminates in a beautiful pointed peak Gez (5696 m), looming over the eponymous village in the Gezdarya Valley. To the west of peak 5975, beyond a deep saddle (about 5350 m), rises the rocky tower of the Agalistan peak 5630. Peak 5975 is the second highest peak in Agalistan, уступая only the unclimbed Shivakhty-III (5981 m). On the northern slope, between peak 5975 and Kongur, and to the north of the East Kongur Pass, at an altitude of 5500 to 5700 m, stretches an inclined plateau, dropping to the north with giant ice falls. The path of the failed Japanese expedition to Kongur (northeast ridge, 1981) passed along the northern edge of peak 5975 through this plateau.

Our team reached the summit of peak 5975:

- on August 19, 2003, at 11:30

- during its traverse from southeast to northwest

- and named it Peak Nikolaeva.

This traverse was developed as a relatively safe alternative to the East Kongur Pass. In our opinion, there is no safer path from the Chimgan Glacier to the Karayalak Glacier.

Nikolaev Viktor Valentinovich (1945–1991)

Electromechanic at MMZ "Opyt" named after A. N. Tupolev. Outstanding Moscow tourist-athlete, designer of numerous tourist equipment samples for ski and mountaineering tourism. Started engaging in sports tourism in the late 1960s at the MGCS DSO "Spartak". His strongest trips were made in the late 1980s as part of groups from the Turk Club of the Moscow Aviation Institute.

1987 (February) — Ski trip of 5B category of difficulty in the Eastern Caucasus with a traverse of the Chehychai podkova and the Bazardyuzyu peak (led by Sorin Boris Vladimirovich).

1988 (February) — Ski trip of 6B category of difficulty in the Eastern Pamir with a first ascent to peak Soviet Officers 6233 m (led by Strygin Sergey Emiliyevich).

1988 (August) — Mountaineering trip of 6B category of difficulty with ascents to peaks Korzhenevskaya and Communism (led by Fomichev Sergey Andreyevich and Stepanov Nikita Rostislavovich). This trip included a first passage of the highest pass in the USSR — Gorbunov Pass (7200 m).

1989 (August) — Mountaineering trip of 6B category of difficulty in the Central Tian Shan with ascents to peaks:

- Mramornaya Stena,

- Khan-Tengri,

- Pobeda (led by Fomichev Sergey Andreyevich and Stepanov Nikita Rostislavovich).

1990 (February) — Ski trip of 6B category of difficulty in the Central Altai, during which a first passage of the Vysotsky Pass (3B) was made, and a complete winter traverse of the Belukha massif was accomplished for the first time (led by Soroka Boris Vladimirovich).

In 1989–1990, together with Valentin Mikhailovich Bozhukov, he was actively engaged in paragliding, independently designing and building one of the first paragliders in the USSR. Among the numerous tourist equipment models designed by Viktor Nikolaev are:

- universal bindings for ski tourism,

- the first rigid crampons in the USSR,

- a tourist jumpsuit of original design,

- a remotely extractable ice screw,

- high-altitude boots made of foam and fiberglass,

- an explosion-proof autoclave based on a standard aluminum pot,

- an asymmetric tent with a central pole,

- a cooking stove for winter tourism and high-altitude ascents,

- soft sled-sledges for transporting goods.

Author of the ideology of ascents to the highest peaks with a special cooking stove. All equipment samples developed by Viktor Nikolaev were characterized by their light weight, simplicity, originality, and thoughtfulness of design elements, as well as the possibility of manufacturing at home. Virtually all these designs remain unsurpassed to this day and rightfully bear the name of their creator.

Viktor Nikolaev died in February 1991 in the area of peak Pobeda under unclear circumstances. After the tragic death of the team leader Igor Razuvaev (during a failed ascent to peak Khan-Tengri), the participants organized the transportation of the body to the helicopter landing sites near the Zvezdochka Glacier. Here, the group split:

- two members went down along the Inylchek River to seek help,

- Viktor Nikolaev remained with the body of his comrade.

Most likely, he intended to attempt a solo ascent to peak Pobeda. On August 10, 1991, Viktor Nikolaev was last seen alive, walking up the Zvezdochka Glacier towards the Pobeda massif. No one saw him again.

Fig. 2. View from the northwest (from the descent side).

Fig. 2. View from the northwest (from the descent side).

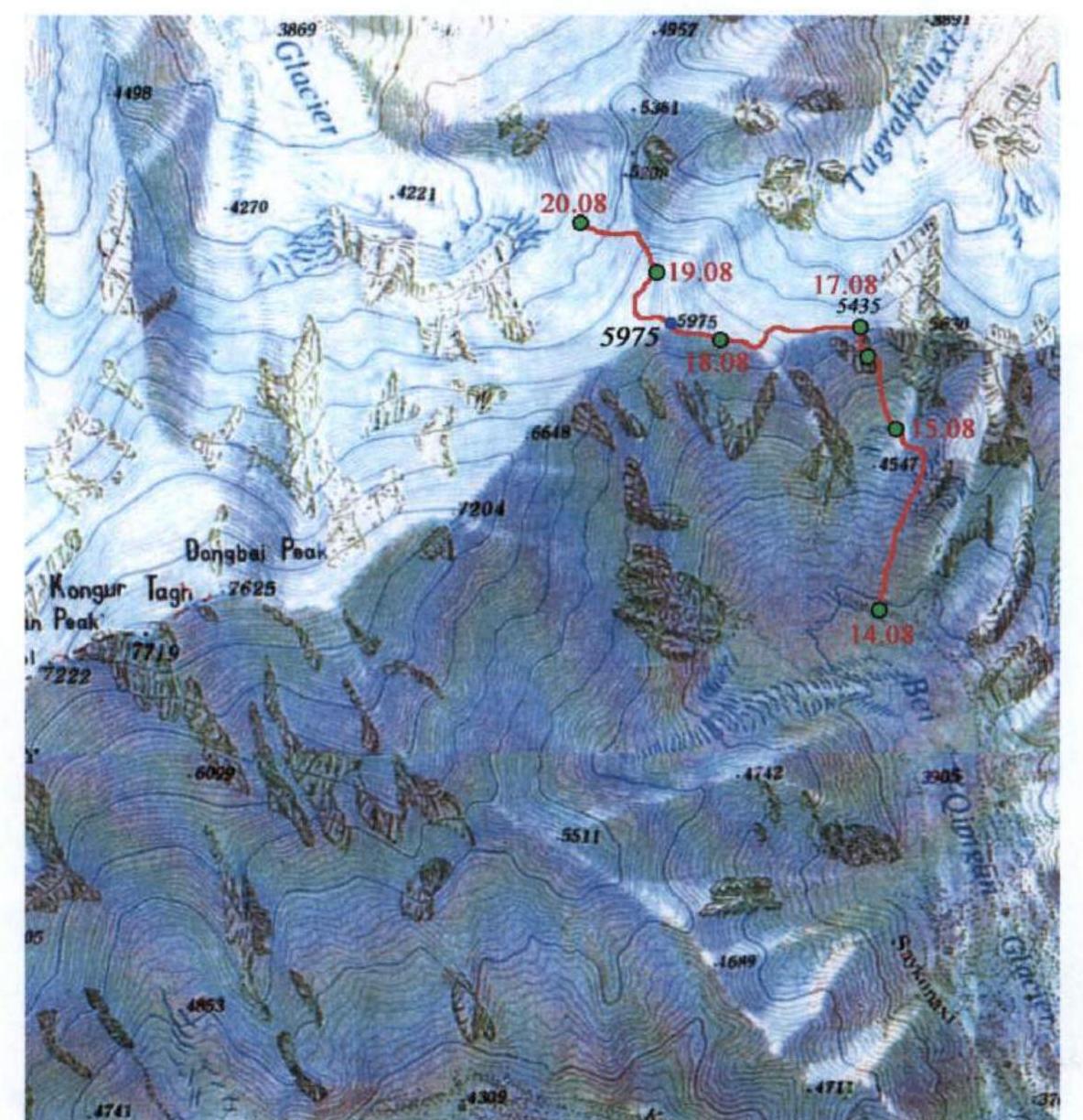

3. Map of the area

The map indicates the dates of camp establishment

| 4. Timetable of the traverse of Peak Nikolaeva | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Content of the day | Heights | Total time |

| August 15, 2003 | Base camp — advance base camp | 4005–4580 | 3 h 25 min |

| August 16, 2003 | Sections R1–R5 | 4580–5210 | 10 h |

| August 17, 2003 | Sections R6–R13 | 5210–5435 | 9 h |

| August 18, 2003 | Sections R14–R21 | 5435–5805 | 7 h 30 min |

| August 19, 2003 | Sections R22–R24 + descent to the North shoulder, see fig. 21 | 5805–5075–5565 | 2 h 30 min + 4 h |

| August 20, 2003 | Descent along the northern edge to the Karayalak Glacier | 5565–4910 | 20 h 30 min |

5. Table of route sections

| N | Name | Rope number | Start height | End height | Photo № | Diff. | Length (m) | Steepness (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Snow slope | – | 4580 | 4720 | 3 | 2 | 280 | 30° |

| 2 | Snow-ice slope | 1–9 | 4720 | 5005 | 3 | 3 | 420 | 40–45° |

| 3 | Oblique traverse along rocks | 10–11 | 5005 | 5052 | 6 | 3 | 100 | 50° wall |

| 4 | Ice slope | 12–14 | 5052 | 5175 | 7 | 4 | 150 | 55° |

| 5 | Snow-ice edge | 15–16 | 5175 | 5210 | 8 | 3 | 70 | 30° |

| 6 | Snow-ice edge with cornice | 17 | 5210 | 5235 | – | 3–4 | 50 | 30° |

| 7 | Snow-ice slope | 18 | 5235 | 5260 | – | 3 | 50 | 30° |

| 8 | Traverse along the ice wall | 19 | 5260 | 5268 | 9,10 | 4 | 50 | 55° wall |

| 9 | Rocks–ice (mixed) | 20–21 | 5268 | 5342 | 10,11,13 | 4 | 90 | 55° |

| 10 | Ice wall | 21 | 5342 | 5350 | 13 | 4–5 | 10 | 60° |

| 11 | Snow-ice edge | 22 | 5350 | 5382 | 12,13 | 3 | 50 | 40° |

| 12 | Snow-ice edge with cornice | 23 | 5382 | 5406 | 12,14 | 3–4 | 50 | 30° |

| 13 | Snow-ice edge | 24 | 5406 | 5435 | 12,15 | 3 | 50 | 35° |

| 14 | Wide snow ridge | – | 5435 | 5450 | 12,16 | 0 | 1000 | <10° |

| 15 | Wide snow shelf | – | 5450 | 5460 | 16 | 0 | 100 | <10° |

| 16 | Snow slope | – | 5460 | 5713 | 16 | 2 | 440 | 30–40° |

| 17 | Snow wall | 25 | 5713 | 5735 | 16,17 | 5 | 25 | 60° |

| 18 | Ascent of the snow-ice ridge | 26 | 5735 | 5752 | 16 | 3 | 35 | 30° |

| 19 | Wide snow-ice ridge | – | 5752 | 5762 | 16 | 0 | 50 | 10° |

| 20 | Snow-ice wall | 27 | 5762 | 5790 | 16 | 3 | 40 | 45° |

| 21 | Sharp snow-ice ridge | – | 5790 | 5805 | – | 3 | 100 | <10° |

| 22 | Wide snow shelf | – | 5805 | 5910 | 16 | 1 | 300 | 20° |

| 23 | Snow slope | – | 5910 | 5930 | 16 | 1 | 40 | 30° |

| 24 | Wide snow ridge | – | 5930 | 5975 | 16 | 0 | 300 | <10° |

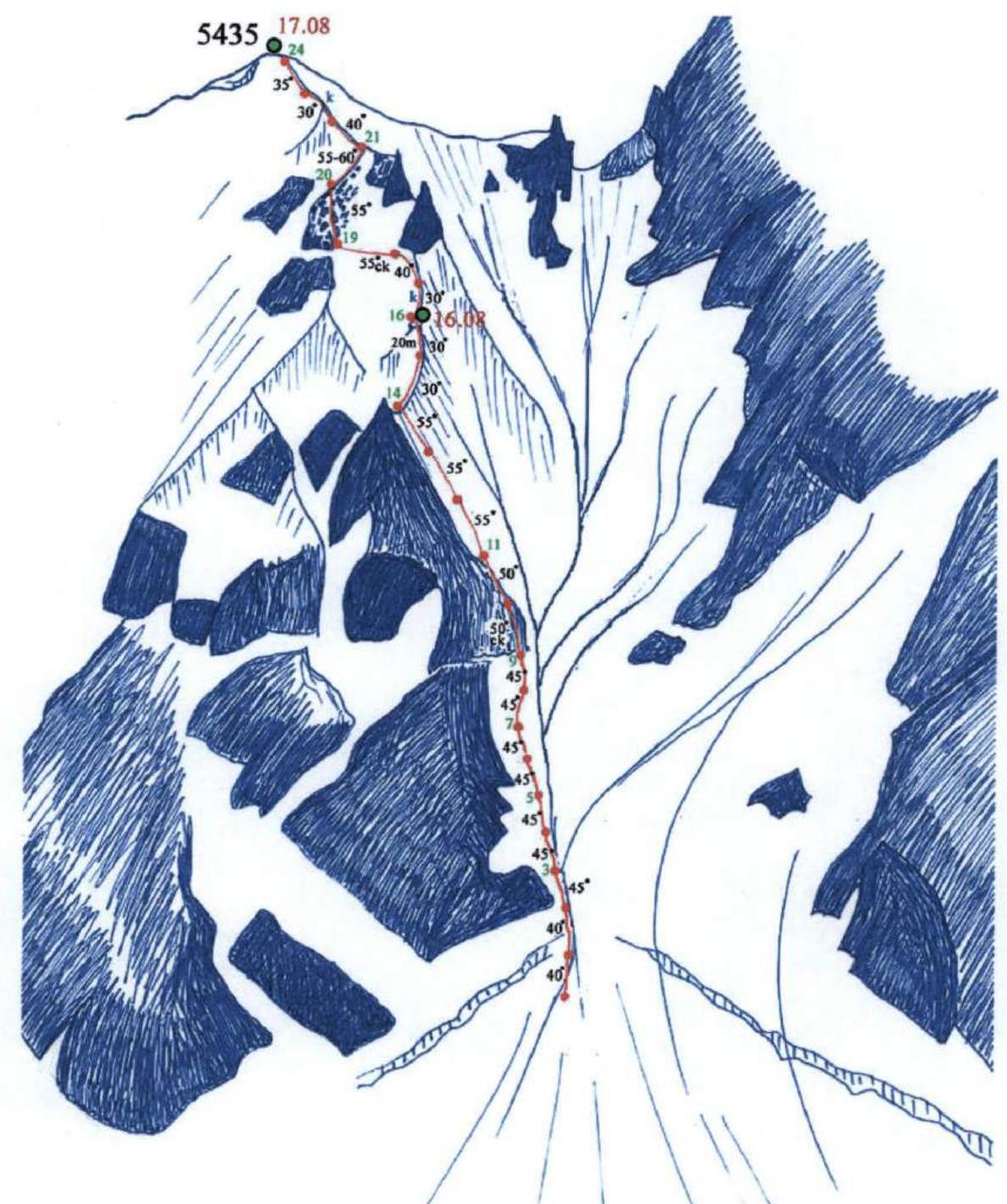

6. Scheme of ascent along the edge

The segment between the red dots corresponds to a 50-meter rope length between anchors, the length of the short section is indicated additionally. Green numbers are rope numbers tied to their ends. Sections are determined by rope numbers according to table 5. On traverses, the steepness of the slope is indicated, not the rope, marked with the inscription "sk". The symbol "к" denotes sections with cornices.

7. Technical photographs of the route

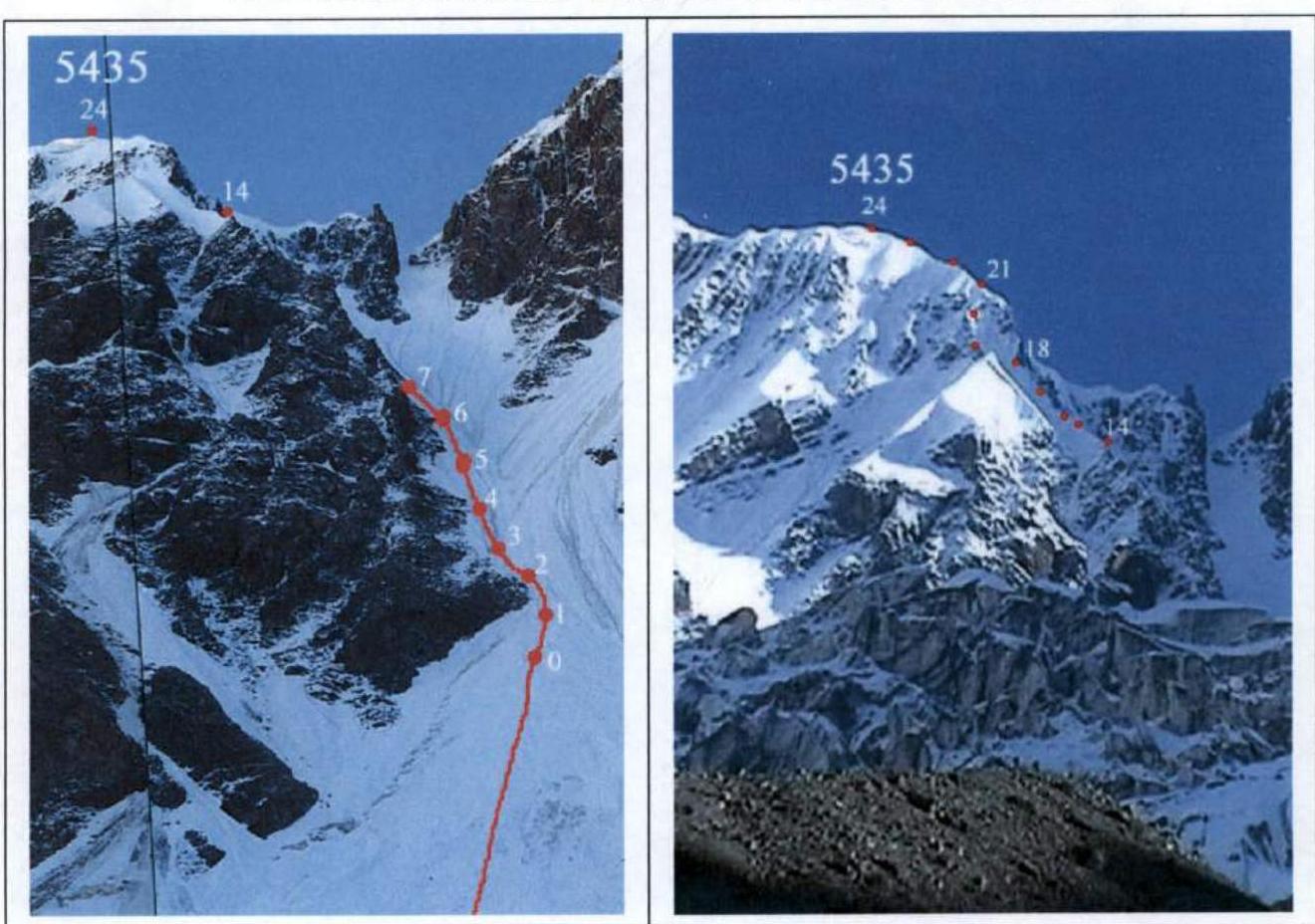

Fig. 3–4. Ascent along the edge. Numbers mark the ends of corresponding ropes.

Fig. 3–4. Ascent along the edge. Numbers mark the ends of corresponding ropes.

Fig. 5. Path along the ridge. Numbers denote the ends of corresponding sections.

Fig. 5. Path along the ridge. Numbers denote the ends of corresponding sections.

8. Excerpts from the report on the mountaineering trip, description of approaches, and traverse of Peak Nikolaeva

August 14, 2003. In the morning, Kongur was visible. We stood on the moraine for a long time, examining the couloirs to the east of Peak Nikolaeva: "Is this peak within our reach?" The couloirs seemed very long — about 20 ropes. And so it turned out; we just didn't know how dangerous they were and that the ascent would require even more complex climbing along the southern edge of peak 5435.

At 10:00, we began our descent to the Chimgan Glacier. In two transitions, we crossed the glacier to the pocket of the left bank of its northern branch. The pocket is green, used for grazing, and a trail clearly leads to it along the left bank of the glacier. After half a transition, we reached a beautiful lake. Lunch. The height here is 3775 m. After another transition and a half — another lake, this time smaller.

Further, the pocket ends, and steep slopes descending into the randkluft begin. So, we went onto the glacier and along the even glacier, covered with grey slabs, we approached the moraine of the glacier flowing from under peak 5630. This detour took about 70 minutes. Climbing from the glacier to its edge, we found two more lakes and set up camp on the shore of the more northern one. Height 4005 m.

August 15. In the morning, an amazing sight — "Golden Kongur". The summit itself is not visible, only the shoulder at 7200 m on its northeast ridge. We moved in the direction of the rock between the wider left glacier and the narrower right one. The cirque we were interested in was hidden behind the icefall of the left glacier.

In two and a half transitions, we approached the foot of this rock, went around it to the left, and climbed onto the ridge behind the rock. Here, the randkluft of the orographic left bank of our wider glacier is already nearby. We put on crampons and, in linked teams, climbed up to the cirque above the icefall in one transition. The steepness in the randkluft is 30°, sometimes up to 45°. Another transition across the broken flat glacier, and we approached the foot of the Agalistan Range wall. Height 4580 m.

August 16. We departed at 8:40. A long snow-ice couloir leads from the glacier to the watershed of the Agalistan Range (see fig. 1, 3, and 4). From below, it is supported by a solid avalanche cone. At the top, the couloir bifurcates. The right branch leads to a saddle west of peak 5630. On the ridge to the left, there is a serious belay. Further left is the western branch of the couloir. In its upper part, the couloir looked very steep. Along its entire length, it was cut by "debris pipes" — gullies carrying stones and avalanches.

We climbed simultaneously in linked teams up to the bergschrund. Underfoot was hard, frozen avalanche snow. Not reaching the bergschrund, we felt uncertain — the avalanche cone is too high, the slope is hard, and the steepness is already around 40°. We started hanging ropes. Along the central avalanche gully, it was easy to dig into the ice, and we fixed the ropes on ice screws. Finally, we passed the bergschrund. In the gully, it was densely packed with frozen snow.

The sun came out, and the first stones began to fall. We climbed out of the gully and started ascending the snowy slope between the main "debris pipe" and the rocks of the western edge (see fig. 3). The steepness increased to 45°, but it became easier to climb as we started to kick steps. We hung ropes depending on the depth of the snow — either on ice screws or on ice axes.

Our comfortable ascent along the snow-ice slope ended by the end of the 9th rope. Ahead and to the left were rocks; to the right was the "debris pipe" adjacent to the rocks. By noon, it "started working" at full capacity. Stones were constantly rolling, and micro-avalanches — mixed flows of snow and water — rushed down with a roar. It was scary not only to cross but even to approach this gully! We had to climb onto the rocks. We hung the 10th and 11th ropes along несложные 50-degree rocks (see fig. 6). We fixed the rope on loops, carefully placing them behind low ledges. The end of the 11th rope was fixed in the ice behind a rocky spur.

From here, both the left and right branches of the couloir were visible. Climbing them was suicidal. Continuous avalanches and rockfalls were thundering in them. Any small snowball or stone provoked a serious flow that fell into one of the tributaries of the central "debris pipe" and rushed far down to the avalanche cone. It was also unclear where to spend the night. The most reasonable thing seemed to be turning left and ascending along the steep ice slope to the southern edge of peak 5435. Perhaps there, on the edge, we would find a place for a camp.

Three ropes of 55-degree ice (see fig. 7) led us to this edge. Here, it is not so steep (30–35°), but simultaneous movement along the edge is too dangerous. By the end of the 16th and last rope for the day, we climbed to a fork where a spur branches off to the southwest from the main edge. Here, on the fork, there was a snowy cushion. This cushion, as we later found out, was the only place on the route for a tent (see fig. 8). Height 5210 m.

We screwed in pitons, hung our backpacks, and then dug into the ice and snow until dark, forming a platform for a half-tent. It was very cramped, with backpacks constantly getting in the way. Yanchevsky was on guard, heroically hanging his rear end over the abyss. We didn't even think about setting up a second tent. Finally, the platform was ready. It was unclear how to set up the tent. Then we figured it out and literally stretched the half-tent over the pile of backpacks and Tatyana, who was operating them. We slept across the tent, attached to a perlon rope passed through it. Falling asleep, I thought: "Will we collapse or not?" "And if we do collapse, what will it look like — a tussling pile of people in a bag-tent, all on a single hook?" "The others will surely fly out; the ice on the ridge is bad, porous!"

Finally, I calmed down — if it was meant to collapse, it would have happened when we were still digging. Now the snow had frozen, and the cornice had become even stronger.

August 17.

Above the tent, two ropes of anchors led to a rocky belay overhanging the ridge. The steepness on the ridge varied from 30 to 40°. The first rope was very unpleasant — it was gentle, but the ridge was narrow, the snow was porous, and there was a small cornice to the east. The ridge was traversed in balance. The second rope, although steeper, was simpler — before the belay, the ridge widened, turning into a narrow slope. We started traversing the belay to the left and immediately found ourselves on a 55–60-degree hard ice slope. We began a traverse (see fig. 9 and 10). Yura hung the first half of the rope, and Misha hung the second half. I don't know how they managed to do it under the weight of their backpacks. I myself barely made it across this section on the anchors, and Yanchevsky, being last, simply fell off!

The rope approached a rocky counterfort, behind which "terrifying couloirs" were visible. At that moment, I felt like I stopped understanding: "What's happening to us?" "Where are we climbing?" "Why?"

Maybe we're climbing here just because we can?

I asked Anton for the height. The GPS showed that we had about 120–150 m to go to reach the watershed. I looked up and saw the snows of the summit above the snow-covered rocks. So, we're on track! We just had to endure two, maximum three, more ropes.

Misha superbly hung the 20th and 21st ropes — straight up along snow-covered (iced) rocks with a steepness of 55° (see fig. 11–13). He managed to climb very cleanly, without dislodging a single stone.

At the end of the 21st rope, the rocks ended, and very steep ice (60°) began. After overcoming this ascent, we found ourselves again on the southern edge of peak 5435, but higher than the belay (see fig. 12 and 13). It turned out that these last three problematic ropes were actually a detour around the belay. Compared to them, the ascent to the summit along the narrow snow-ice edge with a steepness of 30–40° seemed like a simple task (see fig. 14 and 15). Only in the middle of the 23rd rope did we have to fiddle with processing a cornice. At 18:30, we completed the ascent along the last, 24th rope.

On the summit, we found an excellent depression! It was great to be able to drop our backpacks without worrying that they would fall down, walk on flat ground, and finally set up two tents and get a good night's sleep!

Overall, the route turned out to be quite logical and safe. First, we ascended along the couloir as much as possible, then along the southern edge to the summit (see diagram 1). Even the detour around the belay on the edge turned out to be complex but safe. The western, or almost northwestern, exposure of the steep slope ensured ascent along the "shadow," unheated side.

August 18. We departed at 9:40. Peak 5435 was hardly a summit — just a small elevation on the Agalistan Range, distinguished by its southern counterfort (see fig. 1 and 3). For us, it was interesting only as a point of exit to the watershed. Now, our task was to ascend to the multi-peaked massif 5975 and traverse its highest point (see fig. 16). Dan Waugh's slide (see fig. 18) showed that the rocks of the eastern shoulder 5640 of peak 5975 could be bypassed from the north along the ice. From the summit of 5435, we saw a relatively simple exit to the first saddle west of this shoulder (see fig. 16 and 17). Our path led:

- first along a wide ridge,

- then along a shelf under the icefall (see fig. 16),

- then up and slightly to the right, directly to the saddle.

In the glacier fractures, we found passages. From the second half of the ascent, we started trudging heavily. The first person walked 50 steps, then we switched. The ascent to the saddle turned out to be very non-trivial. We thought that beyond the bergschrund, there would be steep ice. It wasn't so. Only a crust glistened, giving away the presence of ice, but it was pressing a meter-thick layer of loose snow to the slope. Climbing a 60-degree slope in such snow is impossible. The first person literally began to sink up to his chest. He had to remove his backpack and perform a miracle. How he managed to climb these 25 m, he himself didn't fully understand until the end. The rest of the participants were pulled up by a block attached to the middle of the rope. The group took about an hour and a half to pass this small section!

While preparing lunch, Oleg and Yura hung 25 m of anchors on the ascent to the ridge. Above, the ridge becomes wide. Then, another ascent — a 45-degree ice slope (40 m of anchors). After that, a very sharp ridge follows, which smoothly led us to the summit of an ice belay. Behind the belay, there is a convenient depression for a camp. Height 5805 m.

August 19. We departed at 9:00. The ice belay on the ridge is easily bypassed from the north (see fig. 16). Then, a simple ascent to the saddle at 5930 follows. From it to peak 5975 stretches a wide and gentle ridge. We reached the summit at 11:30, discussed, and decided to name it Peak Nikolaeva.

At 12:00, we began our descent. Initially, we rushed along the ridge to the north, where there is a saddle, and beyond it, a second, lower peak. However, a high ice fall prevented us from descending to the saddle. So, we returned and headed west towards the extensive snow fields, hoping to bypass the upper part of the northern edge of Peak Nikolaeva along them. On the slope under the dome of the summit, we hung one rope of anchors (ice, 45°, up to 90° at the bergschrund). Below the bergschrund, there is an extended snowy slope with a steepness of about 35°. We descended in linked teams simultaneously through deep snow. Before a huge crevasse, the slope becomes gentler. In the fog, we nearly descended into the crevasse along an 80-meter wall — Yanchevsky had already started, but we timely came to our senses.

We bypassed the crevasse in close proximity to the saddle between Peak Nikolaeva and the northeast ridge of Kongur. From the saddle, we turned northwest and, without significant obstacles, reached an extended snowy slope (see fig. 2). We knew that this slope ends with a terrible ice fall, so we turned right to traverse and exit onto the northern edge of Peak Nikolaeva. Our traverse ended with a small ascent to the shoulder at 5565 m, looming over the northern edge of our peak (see fig. 2 and 21). This is the last gentle spot before the sharp edge. It's already 16:00 — we set up tents, preparing ourselves mentally for the upcoming responsible descent along the northern edge.

August 20. (The weather worsened. Fog, snowfall from the morning. We decided to descend and not wait for the weather, for the following reasons):

- Bad weather in this area often lasts for 3 days, and we couldn't wait that long.

- By the end of the 3rd day, an enormous amount of snow would have accumulated.

- The descent along the edge wouldn't be hindered by bad weather, or almost not.

We approached the northern edge of the shoulder. Down into the fog, a sharp knife-like edge descended. We buried a "parachute" and began the descent (see fig. 2). Up to the rocky belt, we hung 4 ropes + an additional 15-meter piece. Steepness:

- At the start of the first rope — 45°.

- Then — about 50°.

- On the last short section, the ridge becomes gentler, about 35°, but its sharpness is preserved.

There were significant problems with securing the ropes for the descent of the last person. There was no ice as such on the edge. Thin ice plates (2–3 cm thick) alternated with 5–10 cm layers of snow. Neither could we bury a "parachute" nor screw in an ice screw! Long duralumin wedges would have helped, but who would carry such weight on a hike? We had to use our brains and invent "snowy loops." We made them as follows:

- Using a hammer, we drove an ice axe into the slope, then pulled it out and drove it in again at an angle so that the holes met.

- One of the holes was widened to fit a hand.

- Through the narrow hole, we pushed a rep cord with an ice axe, and from the wide hole, we retrieved it by hand.

- We tied the rep cord into a loop, to which the rappel rope (doubled) was attached.

I went last, and oh, the fear I endured! Incidentally, it's worth remembering a rule here — whoever sets up a dangerous rappel point should be the one to rappel. A person should dig their own grave! I remembered my wife and children and tried my best! And I carefully watched the lower end: the doubled rope was always tied to the next anchor below.

We bypassed the rocky outcrop on the edge to the left along the slope.

- One rope went left into a couloir. Ice at 55°, and on a 5-meter rock face, all 90°. The rope was fixed to a loop on a stone buried in the snow.

- The second rope traversed to the right, leading back to the edge below the rocks. The steepness of the slope here was about 45°.

Below the rocky belt, the edge becomes gentler (about 25–30°) but remains just as sharp. There are dangerous cornices on the edge (see fig. 20), so we traversed along the slope close to the edge. The slope is steep, 45°, sometimes up to 50°. A diagonal traverse along such a slope is very inconvenient.

- The 12th rope was hung along a gentle (15–20°) but extremely sharp ridge with cornices and a 55° slope. This was a difficult traverse.

Twilight fell, time was 21:30, and the snowfall intensified.

By the end of the 12th rope, we had already moved quite far from the rocky belt (see fig. 2). As I understood from Yuri Khokhlov's team's video footage (Kongur, northern edge, 2002), there were no more drops below us. The ice wall should smoothly lead to the glacier. So, we decided to turn left and descend along the line of water flow.

We were in for a night descent. This was better than freezing, hanging in a harness on an ice screw. In the morning, after such a night, one could wake up not just unfit for work but in need of evacuation. So, we decided to spend the night working. The main thing was not to rush and do everything extremely carefully, as what mattered now was not the result but the process, which would help us get through the night.

The steepness of the ropes varied:

- The 13th, 14th, and 15th ropes